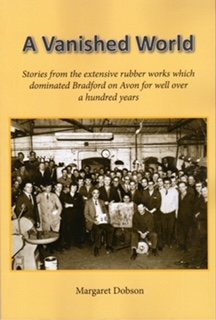

A Vanished World By Margaret Dobson

This latest book published by Bradford on Avon Museum is subtitled “Stories from the extensive rubber works which dominated Bradford on Avon for well over a hundred years”. And, in a sense, this says it all: for the history of the rubber industry in Bradford, you should look to the Museum’s books: The Iron Duke by Roger Clark and Rubber Town by Don Farrell.

This book is a social history, of what it was like to work in the rubber factory and, as so many in the town worked in or for the factory, of its impact on the life of the town as a whole. It is obviously of interest to those who know Bradford now but also more widely as an example of life in and around a works with a pretty enlightened management and a workforce drawn from a small town where people walked to work. There must have been hundreds of such towns across the country; they will all be changed by now. This book is a tribute to a lost way of life.

The first chapter is headed “The heart of the town” and that is just what Spencer Moulton or, later on, Avon Rubber was. Its main premises, the Kingston Mill factory, was right in the centre of the town, with anyone crossing the Town Bridge having to go right past it and with its hooters heard all over the town. It both dominated and defined Bradford. Much of the population worked there: just about everyone must have known at least some of the workers. The workers depended on the local shops and the local shops depended on the workers. And when the factory was closed in 1992, although the workers were offered jobs at the company’s other sites, the “effect on the town’s shops and pubs and other satellite industries was a major blow”.

We are told about how the factory was organised, with a Works Committee set up in 1918 “to give the workers a wider interest in the administration of the firm and to promote a closer feeling of mutual respect ... between the work people and the management”. And as most of the management had worked their way up from the shop floor, everyone knew everyone else. There was a Suggestions Scheme, with employees at all levels encouraged to use their skills and ingenuity to devise better products or better ways of working, with financial awards made to those with good suggestions. And the gatehouse had a vital role, not just as the place where workers clocked on and off, but as a link between workers in the factory and their families without: “This was our link to our family member while he was at work. If there was a family emergency one of us would run down the hill to the Gatehouse and speak to Security who would fetch my Dad or pass an urgent message. They were good like that”.

This last quotation illustrates a key feature of the book. It is built on the recollections of people who worked in the factory and their families, and extensive quotations help to bring vividly to life what the rubber industry in Bradford felt like. Naturally the works evolved during its century and a half ’s existence but the ethos seems to have remained – neighbouring families working there, a hardworking, skilled and versatile workforce; lots of camaraderie (despite some unfunny practical jokes); some tensions between workers and management, such as competing between workers and supervisors on how long it took to do a particular piece of work with the workers trying to spin the time out while the supervisors looked on cynically and checked with a different worker. Some work was varied, some (such as checking the bounce on each tennis ball) unimaginably boring.

Dirt was an unavoidable feature of the works, soot and carbon black. The canteen even provided a separate room for men covered in black powder, so that the grime would spread no further. Smoking in the workshops was dangerous and a sackable offence, but there would be cigarette breaks during which people would sit outside by the river. And there was an incident when people in Lamb Yard were surprised to see men “all stark naked and very agitated” bursting out of the main door – “they had just discovered a large snake in the showers and the result was panic”.

This absorbing book completes its survey of life with the rubber industry by looking at the social side, retirement events, Christmas parties, and particularly the Spencer Moulton Sports and Social Club. Support for various social activities was generous, as was the alacrity

with which the Moultons accepted the philanthropic gift of land for the sports and social club and then subsidised both the buildings and their running costs. Employees were charged only six (old) pence a week for full membership, which they seem to have taken full advantage of.

The book really does give the reader a feeling of what life in the town must have been like when it was dominated by the factory. And it is lavishly illustrated – quite an achievement as cameras were not widely available at the time and photographs tended to be formal records of special occasions.

Angela and David Moss

A Vanished World by Margaret Dobson is published by Bradford on Avon Museum, and can be obtained from the Museum and from Ex Libris bookshop in The Shambles, £10