The housemaid’s tale: a family secret uncovered

An old picture postcard prompted Geoff Andrews to search for the real story behind a life-long estrangement in the mid-19th century

Four of the Hobbs sisters outside the Priory, around 1910. They would have been looking through the gateway at the house pictured below. The bridge in the background, which crossed Newtown close to the Priory Barn, was removed in the 1930s, but had led to the gardens and woodland belonging to the Priory, which stretched up almost to Winsley Road.

It’s an ordinary old picture postcard, the kind of thing people sent with a brief note when the post was central to daily life – an Edwardian version of texting. This one was taken in 1910-11.

It shows the junction of Market Street, Masons Lane and Newtown, Bradford on Avon, with a row of four young women looking at the imposing gates and lodge of the Priory.

The photographer, almost certainly employed by a firm that printed and sold the postcards to local shops, had lugged his heavy glass plate camera and wooden tripod up to high ground and carefully arranged the line, untroubled by traffic it appears.

Just another old picture of old Bradford. The photographer seems to have taken a series of photos that day that became postcards.

Turn this postcard over and it gets more interesting. For a start it was not posted until 30 years later, on 13 September 1940, from Clevedon to Bradford on Avon. And there is no message, just the name and address of the recipient.

Perhaps the postcard was sent by an acquaintance living in Clevedon when they found it somewhere. Perhaps.

The date is significant. Four months earlier the calamity of Dunkirk had sent the country into an invasion panic and 10 days before the postmark, a bombing raid killed 10 people in Albert Road, Clevedon. There were anti- aircraft guns banging away most nights as bombers attacked Bristol, Avonmouth and Portishead. Two planes had crashed nearby and a barrage balloon squad had arrived.

Portishead, the principal radio station for transatlantic calls, was a weak point in a vital link between the British and US governments, so the beach was littered with mines and barbed wire as defences against a commando attack. Not a place where anyone could feel secure. Perhaps it was time to think of moving somewhere safer? Could sending the postcard be in some way connected to those events? Part of evacuation plans?

The four girls on the postcard were sisters, half of the eight children in the Hobbs family (the same family central to the story about the last rope-makers in Bradford, published in the summer issue of Guardian Angel) living at the top of Coppice Hill. The addressee was their mother, Ellen Louisa Hobbs. The sender was probably a cousin who then lived in Portishead.

In 1940 Ellen Hobbs was 72, a tall, spirited woman who didn’t suffer fools. She was already receiving a state pension, hence her frequent exclamation, “God bless Lloyd George”. In her mind he was solely responsible for the old age pension legislation. “Shut thee mouth and give thee ass a chance,” was another of her favourite sayings.

And she is the link, the connection that the photographer unwittingly made between those sisters and events that had taken place about 30 years earlier.

In 1910 the girls’ maternal grandmother Elizabeth was 66 years old and living in Church Street, a couple of hundred yards from their home. But Ellen’s children had been forbidden to speak to her, and the family hardly acknowledged her existence, even though the children had to pass her doorway walking to and from school.

On one occasion at about that time two of the children, twins (probably the middle two of the group on the postcard), were passing granny’s house on their way home from school. It was their birthday, and they wereintercepted outside her house by granny, who gave them a paper bag. Obeying their mother’s rule, they took it home unopened and gave it to Ellen. She flew into a rage and threw it, still unopened, into the fire. The contents of that bag would probably have added a lot to this story.

What the children didn’t know then, or for many years, was that granny, as Elizabeth Fisher, a 23-year-old domestic servant, had allegedly been made pregnant by a son of a prominent local family. Their mother was the result.

Once the pregnancy was discovered, Elizabeth was dismissed from her job as cook/kitchen maid, but received a generous settlement from the family of the alleged father, to provide accommodation and education for the child. According to some accounts the son was disowned and banished, maybe to New Zealand or Australia.

At this point the story becomes more confused. The midwife who had delivered their mother told the girls that during the birth Elizabeth had told her the identity f the father and said it had happened at the Priory, where she worked.

Nothing of this was known to the girls innocently lined up by the photographer looking down the drive to the big house, the place where their mother was conceived.

The family has always thought that Elizabeth Fisher was employed by a branch of the Methuen family living at the Priory, but in the 1860s, when the deed would have occurred, the owner of the house was a QC called Thomas Saunders.

The circumstances of her birth were not, however, the cause of the rift between Ellen and her mother. Indeed, she may not have known about her illegitimacy for some years.

But the cash settlement made Elizabeth a comparatively wealthy young woman – and therefore attractively marriageable. Ellen, meanwhile, was brought up by relatives until she was 11, when she left school, started earning some money and returned to her mother’s home. At around the same time, she also acquired a stepfather: a man well-known to the Bradford magistrates and even better known to local innkeepers.

By the time she was 12, Ellen Louisa had abandoned her mother’s home forever, allegedly after her new stepfather spanked her and her mother did not – or could not – protect her. She had no contact with Elizabeth for the rest of her life.

The identity of Ellen’s father will always be a mystery but here is one intriguing fact:

About a century after Ellen was born, the twins on that postcard were visiting Bradford on Avon from their homes in London and Bristol, and took the opportunity to visit Corsham Court, the long-time home of the Methuen family.

On the tour they were shown the grand staircase and the guide stopped by a portrait painting. She was describing the relevance of this Edwardian belle dame when she stopped, looked at the twins and asked if they were related to the family, because of the striking similarity of the two to the painting. Naturally, they denied anything of the sort.

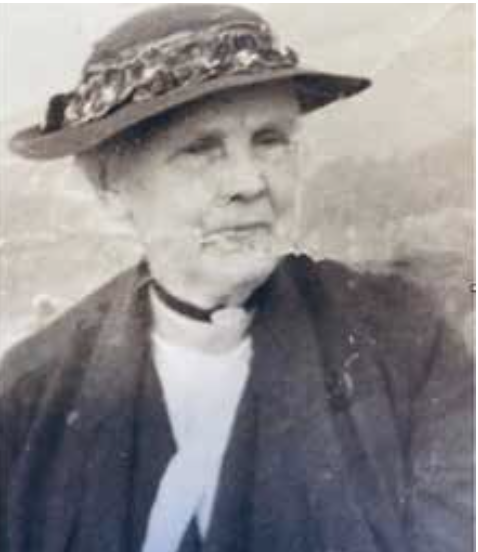

Ellen Hobbs

Three of the four girls pictured outside the Priory in the Edwardian postcard